Reel Recommendations: Lamb & The Lost Daughter

With two new films to look forward to, and after the success of Céline Sciamma’s Petite Maman (an exquisite dream of time and maternity suspended in the forests of childhood play), we wanted to take this opportunity to honour the cinematic imagination of motherhood. There are many famous examples of mothers and/or maternity in the history of cinema: from the pioneering mother of cinema itself, Alice Guy Blanché (1873 – 1963), thought to be the first woman to ever direct a film; and onwards, ranging from the sequined subtlety of ABBA to Abbas Kiarostami, we will voyage through familial film in pursuit of the Cinematic Mother. To get you prepared for Lamb and the Lost Daughter, Reel Recommendations is going to suggest five other vital films that address the role(s) of motherhood. But first, an extra Christmas helping of contextual Cinematernity…

In her directorial debut, The Lost Daughter, the actor turned director Maggie Gyllenhall adapts Elana Ferrante’s novel of the same name, presenting a psychological drama that deftly twists around memory and maternity. Meanwhile, in the startlingly bizarre Lamb, on a remote farm in Iceland a couple decide to bring up a creature that, neither child nor lamb, begins to attract unnerving forces that expose our troubled – and troubling – relationship with nature and its role in, and as, motherhood. Lamb and The Lost Daughter are two wildly different films but both share an umbilical dedication to exploring what it means to be a mother: what constitutes mothering and maternity, and how might film convey such complex experiences.

MOTHER MOVIES: INTENSITY & FEAR

Relatively recently we have seen incredible leading performances tackle the intensity of motherhood: in Frances Macdorman’s iconic role as a mother devastated by loss in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (dir. Martin McDonagh, 2017), let down by the police she takes the gritty pursuit of justice into her own hands; Jennifer Lawrence as the titular Mother!(2017) in Daren Aronofsky’s hysterical spiral of Buñuel influences and sledgehammering biblical symbolism; and the more nuanced cinematic descent into maternal horror that characterises Lynn Ramsey’s astounding, We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), with Tilda Swinton perfectly encapsulating the growing and fearful alienation between herself and an increasingly menacing son.

We could delve further into the shadows and explore the dark canon of ‘Mothers in Horror’: the Freudian dress-up of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), or the less seen, unsettling Freudian drama of Jonathan Glazer’s Birth (2004), the satanic spawn of Rosemary’s Baby (1968); David Cronenberg’s inventive body-horror exploration of mental illness and parenthood in The Brood (1979), or perhaps the terror of the Alien franchise, if interpreted as an ambitiously inter-galactic meditation on the anxieties of pregnancy and birth (also seen in less sci-fi realms, in films like Prevenge, 2016, or the upsettingly gory, Inside, 2007); or more recently, the psychological burden of a strained mother-son relationship faced with the unholy trinity of grief, melancholy and pop-up books, in The Babadook; and, another addition to the ‘mum-fright’ sub-genre, the uncanny and imaginatively nightmarish Goodnight Mommy, in which we encounter the (stylishly conceived) dread of estrangement and a chilling realisation that ‘home’ is no longer a place of familiarity.

AMERICA, MOTHERS & CRIME

Mean Streets, Martin Scorcese’s stark shot of sin and mob-politics, was followed by the madcap mothering road trip of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974). Fresh from her anguished portrait of tormented maternity as Linda Blair’s mother in The Exorcist (1973), Ellen Burstyn plays a widowed mother who embarks on a journey of independence and discovery with her son, Tommy (played by Alfred Lutter). As much about the poisoned fantasies of femininity in American culture as the independence of a single mother, this is an often overlooked gem in Scorsese’s filmography.

Another example of the hard-won wisdom of a single mother in America, can be found in the sage stoicism of Annette Benning’s character in Mike Mills’ charming, 20th Century Women (2016), an intelligently scripted film that looks back to the tail-end of the 70s; evoked with a nostalgic, sun-blushed melancholy that manages to be both wryly humorous and tenderly moving. Mike Mill’s latest, C’mon, C’mon, has just graced our screens here at Tyneside. Continuing in the contemporary, we might think of the darkly comic wit of Tully (2018), following the feverishly exhausted pregnancy of Marlo (a brilliant performance from Charlize Theron) as penned by Diablo Cody (who had previously explored pregnancy in the endearing awkwardness of Juno, 2007); or the comedy heart-break that infuses the mother-daughter relationships in Ladybird (2017) or I,Tonya (2018). We might even throw caution to the wind and consider the joyous karaoke of Mamma Mia! (2007). A less than nuanced singalong that pays glowing tribute to inter-generational relationships between women and the sublime ineptitude of Pierce Brosnan’s vocal cords.

Stepping back from American comedy and into the gun-shot fray of thrillers and noir, there is a long standing tradition of what I will tentatively dub: Mothers in Crime! As a Reel Recommendations exclusive, why not tee up a double-bill of ‘mothering noir’, with the prison and gangster intensity of White Heat (1949), followed by Joan Crawford’s stunning performance in Mildred Pierce (1945). White Heat was directed by Raoul Walsh, who had also starred as an actor (portraying John Wilkes Booth) in D.W. Griffith’s deeply racist epic, Birth of a Nation (1915) – the silent film that was immediately canonized as a founding text of cinema history and embroiled America’s early cinematic evolution with inspiring the formation of the Klu Klux clan (seek out the incredible 1920 riposte, Within Our Gates, a corrective vision from the first African American director, Oscar Micheaux). Raoul Walsh was also responsible for directing John Wayne in first leading role in The Big Trail (1930) and, in White Heat, allows the leading turn of James Cagney to embody a memorably mother-fixated killer. The role of the mother, repression and masculinity all boil in the shadows of post-war angst, creating a darkly psychological noir that revolves around the troubling connections made between murder and maternity. Meanwhile, Mildred Pierce stars the iconic Joan Crawford as an embattled single mother caught in a murder mystery that veers between hard-boiled dialogue and delicious melodrama. Mildred Pierce uses the difficulties of a mother-daughter relationship to interrogate materialism and ambition.

Exploring the ‘Mothers in Crime’ trope further, we could also suggest John Water’s deliriously silly satire, Serial Mom (1994) – starring a gleefully homicidal Kathleen Turner who rampages through the film wielding plates of cookies and kitchen knives with merry abandon. Waters’ film offers a typically tacky insight into the derailed libido of American media, using the murderous matriarch as a way to deconstruct the suburban nuclear family whilst also questioning America’s cultural obsession with serial killers.

A more recent convergence of mothers and crime, can be seen in Bong Joon Ho’s 2009 suspenseful thriller, Mother. After her son is charged with murder, the mild mannered and middle-aged herbalist of the title takes it upon herself to become the amateur detective (a well-worn genre trope) determined to find what the police have overlooked. However, as with most of Bong Joon Ho’s films (from Memories of a Murder, Host, and Snowpiercer through to the famously acclaimed Parasite) genre is always subjected to witty inversions or injected with a mischievous seasoning of chaos. Perhaps the most startling aspect of Mother is the stunning performance of Kim Hye-ja in a depiction of motherhood that burns with an unrelenting need to protect and, as never referred to by name but known only as ‘mother’, she becomes less an individual and more a symbolic or archetypal maternal energy. Driven tirelessly onwards, her identity is subsumed by the demands of her perceived role as a figure of devoted care. Bong Joon Ho reconfigures the familiarity of a maternal impulse into the witty genre dynamics of the detective who will stop at nothing.

EXPERIMENTAL MOTHERS

From mothers in horror and comedy-drama to the twists of noir and genre cinema, there are also artists and filmmakers working outside of narrative conventions to reinvent Cinematernity (to borrow Lucy Fischer’s phrase, author of Cinematernity: Film, Motherhood, Genre) in more experimental realms.

We could consider, News from Home (1976) directed by the Belgian artist, director, screenwriter and film professor, Chantal Akerman. The film uses static shots of New York as the backdrop for an intimate voiceover that reads out letters from Akerman’s own mother in order to create a melancholy synergy between the loneliness of a city and the struggling connections of family. It makes a perfect companion piece to another experimental film, Jonas Mekas’ Lost, Lost, Lost; this is a more socially diaristic and collaged meditation on New York, pieced together from the filmmaker’s perspective as a Lithuanian searching for artistic community. Both films are from 1976, Mekas’ collaged and kinetic methodology draws from 14 years of footage whilst Akerman’s fixed shots render a kind of formalist time capsule over which the less-anchored and more timeless communication of her mother reaches for contact.

These are filmmakers who explore how the form of film, its possibilities as a material trace of time spatially arranged in and as movement, can be controlled and re-imagined. We could also look to the avant-garde documentary innovation of Japanese-American filmmaker, Rea Tajiri. Tajiri’s short film, History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige (1991), uses archival footage, newsreels, photographs, Hollywood film clips, interviews and personal recollection to explore the journey of her mother’s life in, and as, history. It imagines film as a poetic composition, beginning with her mother’s experiences in a Japanese internment camp after the attack on Pearl Harbour, moving through time to evoke the haunted stories that stand in for history and manipulate its representations.

Another experimental film that innovatively uses form in its evocation of motherhood is Abbas Kiorastami’s Ten (2002). Kiorastami’s film is comprised almost entirely from two camera angles within a cramped taxi, unfolding in the structure of ten vignettes that one by one begin to reveal the lives of women in Iranian culture. The driver is herself a mother, and the opening vignette is a conversation with her young son. The bold and ascetic simplicity of Kiorastami’s visual minimalism allows the anecdotes, silence and conversations of each passenger to realistically accumulate into a sense of personal insight. What emerges from this eavesdropping car-journey is a docufiction portrait of patriarchal oppression. There is hope, suffering, banality, resistance and, at the deceptively simple heart of this dashcam odyssey, the relationship between a mother and her son.

Thinking about the experimental observation of maternity from a male perspective (there is not the space here to go into the historically exclusionary histories of what often constitutes the avant-garde, yet it is worth pointing out, just as it is worth pointing out the patriarchal equivalents throughout the film industry), perhaps two of the most striking examples are Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving (1958/9) and Bill Viola’s Nantes Tryptich (1992). Window Water Baby Moving is edited footage from the birth of Brakhage’s own daughter, whereas Nantes Tryptich includes footage of Viola’s own mother dying. Films from, and of, origins and endings. The lensed document of the father / son in relation to the mother…or are they perhaps both artefacts of the intrusive entitlement of a male gaze that stands in opposition to the matriarchal? The reality of such films should not be reductively submitted to the binaries of celebratory or condemnatory judgement – both exist alongside and within the mess of living, standing in relation to mothers in cinema.

As an antidote to the confrontational nature of Brakhage’s probing eye or the elemental ambition of Viola’s tryptic, seek out the quietly glowing warmth of Margaret Tait’s short, Portrait of Ga (1952). In this gently observed film of her own mother, Tait warmly ruminates on landscape, ancestry and poetry creating a humble magic from, and in, the mundane. Both a poet and a filmmaker, Tait was a unique Scottish artist that could articulate the unpretentious grace of landscape and people (drawing constantly from her home in the Orkney Islands) in the pursuit of making what she dubbed ‘film poems’. After watching Portrait of Ga, treat yourself to her exquisite (and only) feature film, Blue Black Permanent (1992) – a beautiful and reflective narrative that connects three generations of women with the haunted memories of a mother and the ocean. Like all of Tait’s work, Blue Black Permanent, conjures poetics from practical observation (perhaps a result of her past as a doctor) creating a kind of film-poetry of grounded modesty that feels truthfully unadorned and yet still open to the rhythms of a dream.

Having sufficiently heaped the suspense for our five recommendations, or tediously scaled the mountain of context, there remains a handful of last thoughts. Three current directors that should really be mentioned in a discussion of mothers and film: Pedro Almodovar (High Heels, All About My Mother, Volver, Pain and Glory…and look out for his upcoming Parallel Mothers); Xaviar Dolan (though many of his films seem to fixate on a mother figure, Mommy is the one to start with); and Hirokazu Kore-eda (perhaps better positioned as a director of family and children, there is still an argument to made for the presence of maternity as a reoccurring interest; you could watch The Truth, 2019, which – quite amazingly – stars Catherine Deneuve and Juliette Binoche as mother and daughter, before returning to the Palme d’Or success of Shoplifters, 2018, with its themes of adoption and family). So, finally, we arrive at our REEL RECOMMENDATIONS…

We Recommend

Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk, 1959)

Douglas Sirk, undisputed king of melodrama: that is, melodrama not as an exaggeration of reality but as reality uninhibited, allowing emotions to pour through the technicolour swoon of America’s illusory dreams of domestic happiness. The poisoned chocolate box of sunny suburbia, its apple-pie and white picket fences, immaculate lawns and waving neighbours – everything conforming to a lie of post-war contentment; all of this was trembling behind Sirk’s confections, a German director who saw through the American dream to the festering anxieties and repression. Behind David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and the small-town surrealism of Twin Peaks, is the presiding spirit of Sirk.

Imitation of Life was Sirk’s last film, and for many, his crowning achievement. The film explores the relationship between two single mothers and their children. One mother (‘Lora Meredith’ played by Lana Turner) is a blonde, white woman dreaming of Hollywood success while the other is a Black woman named Annie Johnson (a heart-breaking performance by Juanita Moore) whose daughter’s fair skin means that she can ‘pass’ for white (a concept at the centre of this year’s Passing, which played at Tyneside and is now available on Netflix). The film creates a complex portrait of maternity through painful contrast, exposing the searing hurt, division and injustice of racism and class. This is a visually lavish and powerfully acted masterpiece that foregrounds two mothers in a devastating microcosm of American society.

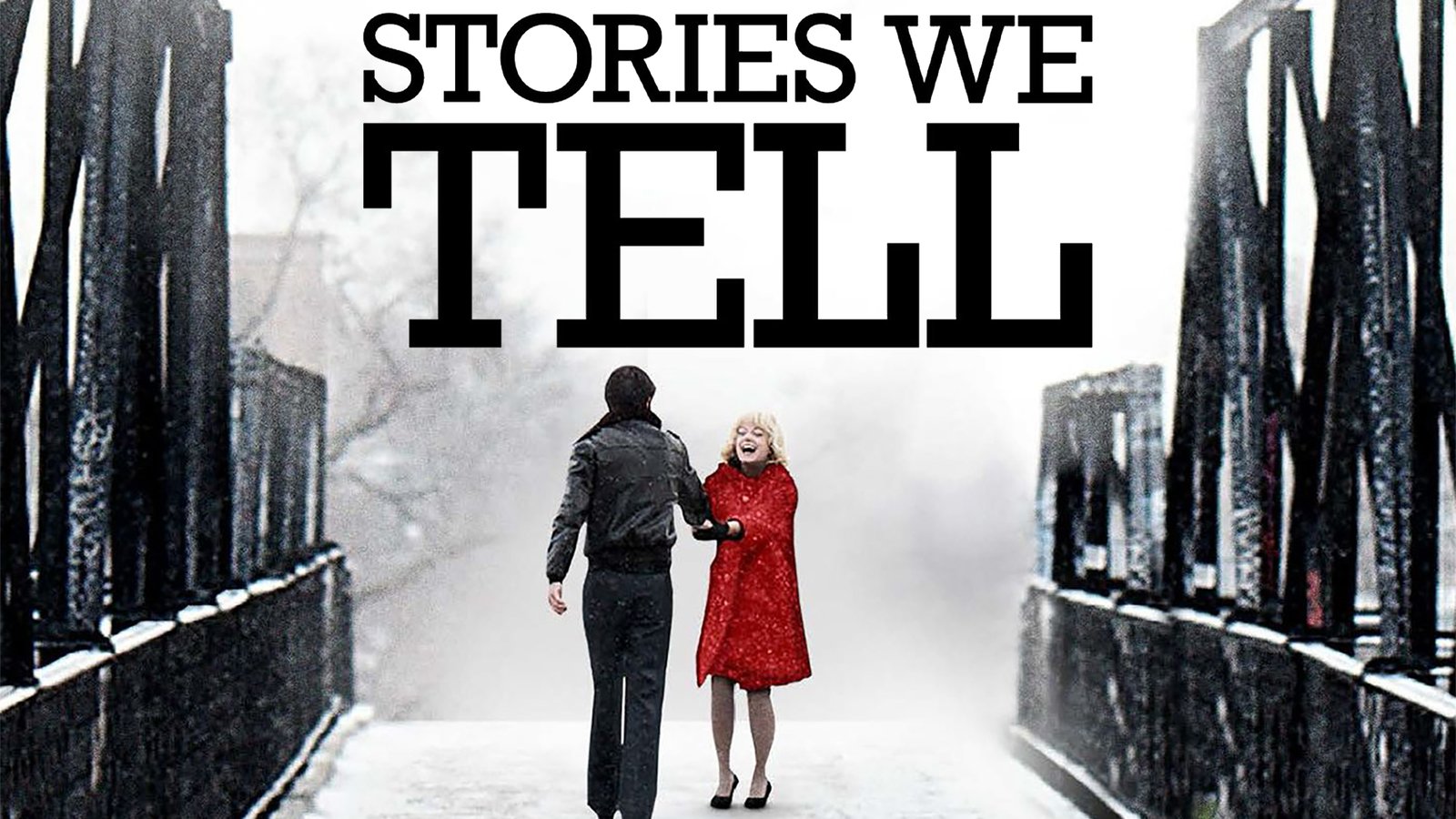

Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, 2012)

There are plenty of stunning documentaries that we could have chosen that revolve around mothers: from the ramshackle eccentricities of cult masterpiece, Grey Gardens (1975), to the 2021 inter-generational feminist celebration of African American mother-figures, In Our Mother’s Gardens. There have also been important strides in the representation of Trans maternity in two recent documentaries, A Deal with the Universe (dir. Jason Barker, 2018) and Seahorse (dir. Jeanie Finlay, 2019), both of which played to great success at Tyneside Cinema.

Finally, however, we decided upon a documentary that wove together recollections, family footage and recreated family footage in a daughter’s search to understand a sense of mystery that surrounds her own mother. Imaginatively constructed through a collage of interviews and the nostalgic glow of home video, Sarah Polley’s fascinating and deeply moving film allows the viewer to encounter certain secrets and revelations in unison with the filmmaker’s growing understanding of her mother’s life. This is a sensitive and intimate portrait of the narratives we build into family mythology, the ways in which memory fabricates and falters, and how the act of remembering (contingent on forgetting) will always create multiple versions of a life.

Daughters of Dust (dir. Julie Dash, 1991)

Famous for being the first feature film directed by an African American woman to gain theatrical release (restored and re-released in 2016), and later the main source of inspiration for Beyoncé’s Lemonade video, Dash’s seminal film invents its own poetic theatricality connecting African spiritualism with a dream-like conjuring of matriarchal community.

Set in 1901, the film imagines a village on the island of St. Helena where the descendants of slaves have continued to uphold and further establish African culture – kept in a kind of timeless resistance to America. Not only does this film cultivate a circular slipping of non-linear narratives to coalesce with the in-the-round theatricality of its cinematography but its veneration of African culture as a mothering force, creates a unique vision for which time and space (narrative and setting) are subject to the rich traditions of spiritual maternity. This is a celebratory dream of genealogy and resistance, where the figure of the mother exists as a source of spiritual and social power.

Second Coming (dir. debbie tucker green, 2014)

debbie tucker green’s beguiling drama is a quiet miracle of a film that places the suggestion of the ‘immaculate conception’ within the mundane reality of a middle-aged couple, bringing a poetic mystery to inter-personal relations and the potential symbolism of the everyday. debbie tucker green (who defiantly preserves a lower-case, all on one level, spelling of her name) is one of Britain’s leading playwrights (born bad, random, ear for eye), known for intelligently pairing themes of astute political engagement and racial injustice with a hybridised and experimental use of form and style.

In Second Coming, Nadine Marshall delivers an incredibly nuanced and sensitive performance as the unexpectedly pregnant mother, with a taciturn Idris Elba as her partner; both performances are realised with a wholly believable naturalism that lends a greater strength to the film’s subtle magical realism. Fears of pregnancy, maternal loss and the unspoken communications that constitute our experiences of love and family all quietly build into a genuinely original film of mesmeric ambiguity.

Mother and Son (dir. Alexander Sokurov, 1997)

A frail mother is carried by her son, there is a winding path, a gently warping verdant hillside, the whispering of leaves overhead, a window through which light changes and blossom appears on the trees outside, an outstretched hand, exhaustion, devotion, a sigh, whispered words, silence and the slow dream of time moving. The profound and sparse poetry of this film reaches a kind of bare religiosity, the complete and vulnerable ritual of true care suffuses every somnambulant moment with an aching, almost elegiac, compassion.

Very little happens: a mother sleeps and is carried by her son, he walks along a winding path and later sits beside her, lies beside her…time is spent together, is felt in its dreamy haze of landscape and whispering. And yet, despite the apparent absence of conventional narrative or perceivable events, the film reaches a spiritual depth that is at times overwhelming. Few other works in cinema manage to approach the ineffable and elemental bond that can exist between a mother and her child, just as few other films are able to so poignantly express the reversal of roles that time brings to parenthood. Mother and Son exists in a world and a time of its own; a lyrical prayer to, and from, the journeying transience of caring for a life.

Visit our Letterboxd list of this edition of Reel Recommendations here.